On 25 January, the Welsh Government launched a consultation relating to a potential Geological Disposal Facility (GDF) for nuclear waste in Wales. This runs in parallel with the UK Government Consultation on the same issue. Lesley Griffiths, Cabinet Secretary for Energy, Planning and Rural Affairs issued a written statement accompanying the consultation launch highlighting that a GDF would only be sited in Wales if a community voluntarily hosts it:

Although the Welsh Government supports geological disposal, this does not necessarily mean a GDF will be built in Wales or that the Welsh Government will seek to have a GDF built in Wales. The Welsh Government has not considered or identified any potential sites or communities for a GDF in Wales. Our policy is very clear, a GDF can only be sited in Wales if a community voluntarily comes forward to host it.

What is the GDF for?

There are many sources of radioactive waste in the UK. These range from energy production to medical diagnostics and treatments. The waste produced has a range of levels of radioactivity and lifetimes. While as much material as possible is reused or recycled, some needs to be securely stored for thousands of years to protect people and the environment. Currently, the waste destined for the GDF is being reprocessed at Sellafield, Cumbria or put into temporary storage.

Since the early days of the UK nuclear programme in the 1950s, a vast amount of radioactive waste has been produced. More than 90 % of this is low level waste, such as paper and plastics from hospitals and research facilities. The Low Level Waste Repository in West Cumbria is used to dispose of this material, storing it at surface level. There are around 650,000 m3 of higher activity waste (enough to fill nearly half of the Principality Stadium) that would be disposed of in the GDF. This waste mainly comprises of nuclear reactor components and material from nuclear fuel reprocessing.

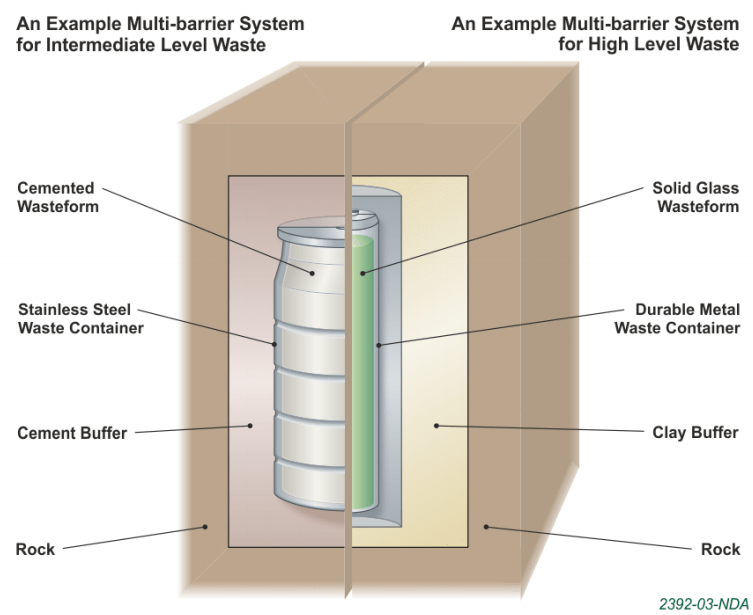

The GDF would encapsulate the waste, with several barriers to prevent any possible leaks (diagram below), and bury it 200-1000 m deep in a geologically stable area. This would ensure that the waste could be safely left without further human intervention, although monitoring around the GDF could continue to ensure that no leaks occur. This was the approach recommended by the Committee on Radioactive Waste Management, as the best-available approach for long term management with lower risks than the alternatives.

Previous searches for a GDF site

The search for a site for a GDF began in 1982 with a long list of sites across the UK. Eighteen of the sites were in Wales, including the Trawsfynydd and Wylfa nuclear power stations. None of the sites in Wales made the shortlist because of their location or geology. This process was abandoned in 1997 when the Secretary of State for the Environment refused to allow exploratory drilling at the chosen site.

In 2008, the UK Government published a white paper on a framework for implementing a GDF. In the same year, Cumbria County Council expressed interest in hosting the GDF. Following a campaign by environmentalists and evidence from independent geologists citing concerns over the suitability of the geology in the county, the Council rejected the GDF in 2013. This resulted in a new white paper in 2014 to restart the search for a GDF location.

Due to changes in facility design and technology, new locations and geologies can now be considered. As a result the previously rejected or not considered sites may be included in the new search process.

Policies outside England and Wales

GDFs are being planned in several countries, with sites selected in France, Sweden and Finland. The siting processes in these countries were reviewed by the UK Government in 2013. The successful examples of siting have demonstrated the necessity for community engagement.

The Scottish Government has chosen to not build a GDF, but instead to use near surface storage designed to last around 150 years, to store higher activity waste. This facilitates easier retrieval of material to allow for future technological solutions to waste treatment or disposal. Eventually a longer term solution will be required.

Not all waste can be safely stored this way, so some may be sent to the GDF built for the rest of the UK. Spent fuel, the most radioactive product from nuclear energy, is currently sent to Sellafield from Scotland for reprocessing.

The Welsh Government’s view on the approach taken in Scotland is laid out in the consultation document :

Alternatives to geological disposal, such as ongoing surface storage, do not provide a permanent solution and leave future generations to take responsibility for the safe and secure management of these materials. The Welsh Government does not consider that ongoing surface storage would meet our responsibility to future generations or meet the requirements of the Well-being of Future Generations Act.

The Host Community

The new search will emphasise a community first approach. Communities that are interested in hosting the GDF will be invited to come forward. Additionally, the withdrawal process from hosting a GDF will be clearly specified. It is expected to take around 15-20 years from the start of community engagement to establish support and identify a site before construction begins.

The Welsh Government is consulting on the process of engagement with communities that are interested in hosting a GDF. This includes how a community will be defined and how the funding offered to potential host communities will be spent. The funding offered to each community is up to £1 million per year during engagement and up to £2.5 million per year during borehole investigations. This is in addition to the investment in the GDF, which is anticipated to bring 600 long-term skilled jobs and 1000 additional jobs during construction.

Response

The proposed GDF and the consultation have been subject to controversy, with some organisations supporting the motion to deal with nuclear waste in the long-term and others concerned about how well informed communities are.

Professor Iain Stewart, director of the Sustainable Earth Institute, Plymouth University, said:

A geological disposal facility is widely accepted as the only realistic way to dispose of higher activity nuclear waste for the long-term.

Doug Parr, chief scientist to Greenpeace, criticised the community payments:

Having failed to find a council willing to have nuclear waste stored under their land, ministers are resorting to the tactics from the fracking playbook - bribing communities and bypassing local authorities.

The Research Service acknowledges the parliamentary fellowship provided to Robert Abernethy by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), which enabled this blog to be completed.

The Research Service acknowledges the parliamentary fellowship provided to Robert Abernethy by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), which enabled this blog to be completed.

Article by Robert Abernethy, National Assembly for Wales Research Service