This is essentially what the Welsh Government has asked the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to help answer, a decade after the education system showed ‘evidence of systemic failure’ as the Welsh Government itself recognised.

The OECD will soon be publishing its latest report on Wales’ progress and the Minister for Education, Kirsty Williams MS, will subsequently make a statement in Plenary on Tuesday (6 October). Publication of the OECD’s report was due in March but this was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

What has the role of the OECD been so far?

The OECD’s influence on the Welsh Government’s education policies has been felt since the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2009 results delivered what the then Education Minister called ‘evidence of a systemic failure’ and a ‘wake up call to a complacent system’.

Successive PISA results in 2012 and 2015 showed little improvement. The OECD was called in to advise on solutions, undertaking a review in 2014 and a ‘Rapid Policy Assessment’ in 2017 to guide the Welsh Government’s education strategies. Our previous articles of November 2019 and June 2016 provide background to all of this.

Wales’ results in PISA 2018, published in December 2019, provided some encouraging signs of progress, with the Minister describing them as ‘positive, but not perfect’. Wales PISA scores are no longer statistically significantly different to the OECD average in each of three main domains (reading, mathematics and science), although they remain the lowest amongst the UK nations.

The Minister told the Children, Young People and Education (CYPE) Committee in February 2020 that she had invited the OECD ‘in the tail end of last year’ to review progress against the Welsh Government’s school improvement action plan, Education in Wales: Our National Mission.

What is the Welsh Government’s approach to school improvement?

Education in Wales: Our National Missionsets out the Welsh Government’s school improvement policies between 2017 and 2021. Curriculum reform is integral to the action plan and ‘enabling objectives’ include developing a high-quality education profession and greater self-improvement by schools.

The Welsh Government is spending an additional £100 million on raising school standards in this Senedd term (2016-2021), compared to the previous Senedd. This additional money is being targeted at strategic improvement priorities rather than providing additional funding for schools’ core budgets which was the previously adopted approach between 2011 and 2016. Our previous article from October 2019 explains the complex arrangements for funding schools in Wales.

As has been discussed in CYPE Committee sessions, the disruption to schooling from COVID-19 and the disproportionate impact this could have on disadvantaged children brings an added complexity to the Welsh Government’s approach to school improvement.

’Too many secondary schools are still causing concern’

Local authorities and the Welsh Government have powers to intervene in ‘schools causing concern’ under six ‘grounds’ set out in the School Standards and Organisation (Wales) Act 2013 or if the inspectorate, Estyn, has judged that a school requires Significant Improvement or Special Measures (the two statutory intervention categories which schools can be placed in following Estyn inspections). The Welsh Government issued statutory guidance in 2017 on ‘schools causing concern’ and how local authorities should use their powers of intervention.

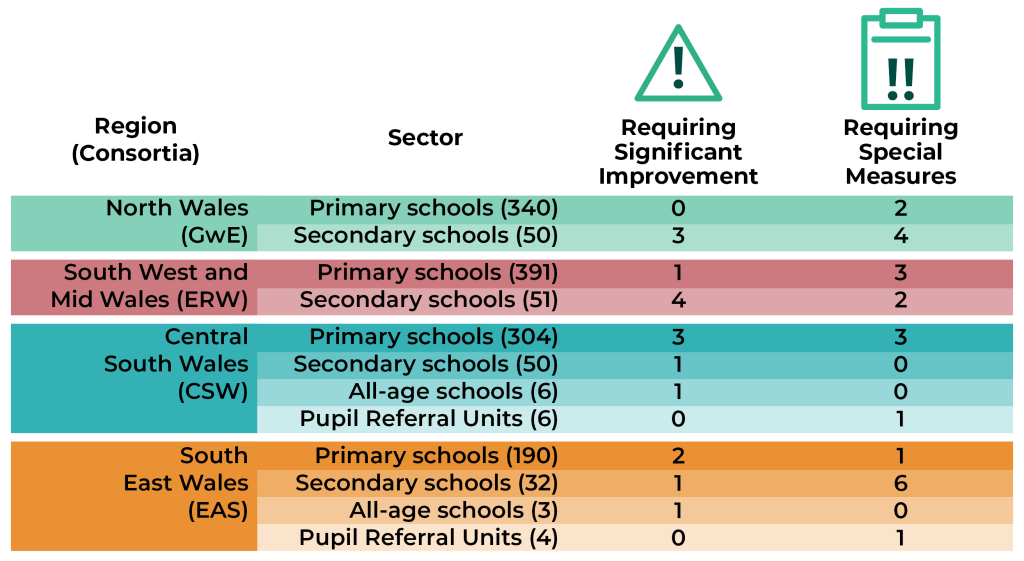

‘Too many secondary schools are still causing concern’, according to the Estyn Chief Inspector’s 2018/19 annual report. Whilst standards were good or better in 81% of primary schools inspected in 2018/19, this was true for only 45% of secondary schools. Currently, 9 secondary schools and 2 all-age schools require Significant Improvement while 12 secondary schools require Special Measures. Given there are just under 200 secondary schools in Wales, this means that over 10% of secondary schools are currently in one of the statutory intervention categories. A further 12% are under the less intensive category of formal Estyn review.

This suggests that secondary school pupils in Wales have only a 50/50 chance of going to a school that is good or better, while almost a quarter attend one which requires Estyn review or statutory intervention and over one in ten pupils go to schools judged as failing.

How many primary, secondary schools and PRUs are in the statutory categories?

The infographic below shows the number of schools and pupil referral units (PRUs), across each education region, that are currently in either of the two statutory intervention categories. The numbers in brackets represent the total number of schools in each region.

Source: Information provided by Estyn, September 2020

Source: Information provided by Estyn, September 2020

Back in December 2018, the Chief Inspector warned that schools causing concern are ‘not identified early enough’ and ‘there is a need to do something urgently’ about these schools, particularly secondary schools. The Minister told the CYPE Committee in February 2020 (PDF) that the Welsh Government is trialling a multi-agency approach to schools causing concern, aiming to have ‘strong partnerships across the middle tier’, including local authorities, regional consortia and Estyn. The pilot involves eight secondary schools: two in each of the four regions.

‘The “poverty gap” has not narrowed’ and ‘typically widens as learners get older’

This is another stark finding from the Chief Inspector’s 2018/19 annual report, based on Estyn’s observations of what has happened to the gap between the attainment of pupils eligible for free school meals (eFSM) and their peers over the past decade.

- The gap between the proportion of eFSM pupil and other pupils achieving the Level 2 threshold inclusive (5 or more A*-C GCSEs, including English/Welsh and Maths, or the vocational equivalent) reduced only very slightly from 31.9 percentage points in 2009 to 31.3 percentage points in 2016. This is because both eFSM pupils’ and non eFSM pupils’ attainment rose at a fairly similar rate. (StatsWales)

- Since 2017, when there were changes to how performance measures are calculated, the gap in attainment of the Level 2 threshold inclusive has remained pretty much the same: from 32.3 percentage points in 2017 to 32.2 percentage points in 2019. (StatsWales)

- The gap in the proportion of eFSM pupils and other pupils achieving the expected outcome in English/Welsh, Maths and Science at the end of Key Stage 2 (age 11) in 2019 was 15.5 percentage points. The gap at the end of Key Stage 3 (age 14) was 19.9 percentage points, whilst the Level 2 threshold inclusive gap at the end of Key Stage 4 (age 16) was 32.2 percentage points. The FSM attainment gap is therefore wider amongst older cohorts. (StatsWales)

The lack of progress in narrowing the gap between eFSM and non-FSM pupils comes despite over £475 million being invested by the Welsh Government in the Pupil Development Grant (PDG) since 2012. The PDG supplements schools’ budgets according to their eFSM headcount. Estyn reports that two thirds of schools use the PDG effectively to mitigate the impact of poverty.

However, the Chief Inspector has also said that in a context of austerity, perhaps schools have been ‘running to keep still’. Furthermore, PISA 2018 results indicate that the attainment gap between pupils who are disadvantaged by poverty and their peers is smaller in Wales than the OECD average and the gap in England.

What is happening to school accountability and performance measures?

Self-evaluation is an increasing feature of the Welsh Government’s approach to school improvement. This is influenced by the OECD’s observations that effective self-evaluation by schools is a prominent feature of high-performing education systems around the world.

The Welsh Government has also made changes to the information that is published and reported around school performance. However, the Minister emphasises (PDF 588KB) she is not seeking to ‘hide away data’ and the aim is to have smarter accountability not less. For further information on what is changing, see our October 2019 blog.

These issues were raised by the CYPE Committee with the Minister and with Estyn earlier this year.

When will the OECD’s report be available and when will Members of the Senedd discuss its findings?

The Minister for Education will make a statement and answer questions in Plenary on Tuesday (6 October) regarding the OECD’s review. This will be broadcast on Senedd TV and a transcript will be available on the Senedd's Record of Proceedings.

Article by Michael Dauncey, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament