Brexit is bringing about the biggest changes to the UK’s immigration system in decades. A new system will be needed when free movement for EU citizens ends.

Immigration is not a devolved issue, but 80,000 EU citizens live in Wales, and some sectors (like manufacturing, social care, education and health) are reliant on EU labour.

This article looks at the current immigration system, proposals for a new system, the impact on Wales, the EU Settlement Scheme and the rights of EU citizens in a no deal scenario.

The current UK immigration system

There are two distinct immigration systems in the UK: one for EU, EEA and Swiss citizens, (for ease, these will all be referred to as ‘EU’ citizens in this article) and a separate system for non-EU nationals.

Currently EU citizens have the right to live in the UK for up to three months without being subject to any conditions. After three months, they have the right to reside if they are workers, looking for work in the UK or have sufficient resources to reside.

For non-EU citizens, there are different work visas available for different purposes. Most work visas are part of the UK’s ‘points-based system’. The system has five tiers,each with sub-categories:

- Tier 1 for highly skilled individuals;

- Tier 2 for skilled workers with a job offer to fill gaps in the workforce (this includes a salary threshold of £30,000 and is restricted to higher skilled workers);

- Tier 3 for low skilled workers to fill temporary labour shortages (this Tier has never been used as gaps are currently assumed to be filled by EU nationals);

- Tier 4 for students, and

- Tier 5 for temporary workers and young people covered by the Youth Mobility Scheme

Tier 2 (General) is the main visa category for bringing skilled non-EU workers to the UK. It has been capped at 20,700 visas a year since 2017. Doctors and nurses were exempted from the cap in 2018, after demand for permission to sponsor skilled workers frequently outstripped supply.

Employers applying for sponsorship for Tier 2 (General) visas must prove that they have tried to recruit from the resident workforce (called the resident labour market test).

The shortage occupation list (SOL) is an official list of occupations for which there are not enough resident workers(including EU nationals) to fill vacancies. The majority of the jobs on the SOL are in health and engineering. The UK list is supplemented by a separate list for Scotland. Employers searching for employees for jobs on this list do not have to undertake a resident labour market test.

To employ non-EU nationals in Tier 2, employers have to pay the UK Government an Immigration Skills Charge, which is generally £1,000 a year per worker. Migrants may also have to pay an Immigrant Health Surcharge (IHS) to be able to use the NHS.

The current non-EU points-based system has been criticised for being unduly complex, burdensome, costly and ill-suited to the needs of its users(see page 11 of this House of Commons Library briefing for detail).

Proposals for post-Brexit immigration

After Brexit, a new immigration system will be required. The previous and current UK Government committed to ending free movement.

Following recommendations from the Migration Advisory Committee report (published in September 2018), the previous UK Government under Theresa May published itsimmigration White Paper in December 2018, with a 12 month consultation period.

The previous Government’s White Paper proposed to:

- add EU citizens directly into the current points-based system under Tier 2 for skilled workers with job offers, with no preferential treatment;

- expand Tier 2 by: removing the 20,700 visa cap and the resident labour market test; reducing the skills threshold to RQF+ level 3 (A-levels or equivalent); retaining a salary threshold (but consulting on the current £30,000 – the Migration Advisory Committee is currently exploring options), and considering a shortage occupation list (SOL) for Wales, and

- not provide a specific route for low-skilled workers, but introduce a range of transitional measures. It also proposes some modest changes to post-study work, and retaining but reviewing the Immigration Skills Charge.

But the new UK Government under Boris Johnson recently stated that “improvements to the previous government’s plans for a new immigration system are being developed”. The Migration Advisory Committee has been tasked with developing plans for an “Australian style points-based immigration system”, but it is not yet clear what this might entail.

The UK Government recently announced changes to post-study work visas which would allow international students to stay in the UK for two years after graduation. Graduates currently have four months to find a job before having to return to their own country.

The Government also announced plans to: introduce “tougher UK criminality thresholds”, remove the EU customs channel at UK borders, remove rights for “post-exit arrivals to acquire permanent residence under retained EU law”, and “rights for UK nationals who move to the EU after exit to return with their family members without meeting UK family immigration rules”, and introduce blue passports.

Impact of White Paper proposals on Wales

A Welsh Government-commissioned paper from March 2019 by Professor Jonathan Portes estimated the impact of the White Paper’s proposals on Wales.

The research found the challenges of the ageing population to be more acute in Wales than elsewhere in the UK, with slower growth in the overall population but faster growth in the over-65s. Meanwhile, the 16-64 population is projected to shrink by 5% by 2039. It argued that lower than projected migration might exacerbate these issues.

Professor Portes estimated that under the White Paper’s proposals, almost two-thirds of EU workers currently in Wales would not be eligible for a Tier 2 visa with a £30,000 salary threshold, leading to a 57% reduction in EU immigration to Wales over 10 years.

He estimated that it would result in “a hit to GDP of between roughly 1 and 1.5% of GDP over ten years [in Wales], compared to 1.5 to 2% for the UK as a whole.”

The manufacturing, social care, hospitality, health and education sectors in Wales are most likely to be affected by the White Paper proposals as they rely heavily on EU immigration, but many jobs fall under the £30,000 salary threshold.

Portes concluded that it is difficult to make a case for a regional migration system, as migration in Wales is not significantly different to the rest of the UK. He recommended that the focus of the Welsh Government’s response to the White Paper should be on pressing for a lower salary threshold for the UK as a whole.

Welsh Government policy

The Welsh Government set out its detailed approach to immigration in 2017. It called for a preferential system of immigration for EU citizens, and said that “should the UK Government pursue a restrictive immigration policy which would be detrimental to Wales, [it] would explore options for a spatially-differentiated approach that would be more fitting to Wales’ needs and interests”. It also called for there to be no further restrictions on EU students.

In response to the White Paper proposals in June 2019, the Brexit Minister Jeremy Miles said he was “extremely concerned that such a restrictive immigration system after Brexit would lead to real skills shortages in our key economic sectors”, and called on the UK Government to drop the £30,000 salary threshold.

The Welsh Government’s EU Citizens Grant Scheme provides short term for funding for projects in Swansea, Merthyr, Newport and north Wales to help EU citizens apply to the EU Settlement Scheme.

It also announced a package of support for EU citizens in Wales to help them apply for settlement, including a new website.

The Welsh Government’s recent no deal action plan covers strategic risks like workforce impacts for the public sector and businesses, legal uncertainty for EU citizens, and the risk of UK citizens returning from the EU in large numbers.

EU Settlement Scheme

The UK Government established the EU Settlement Scheme (EUSS) because, in most cases, EU citizens living in the UK will no longer have a legal right to reside in the UK once it leaves the EU and free movement ends. Irish citizens do not have to apply to the EUSS, and can reside in the UK indefinitely under a separate arrangement.

Applicants to the EUSS will either get ‘settled’ or ‘pre-settled’ status, depending on how long they have lived in the UK.

Settled status is available to those who have lived in the UK continuously for five years by 31 December 2020 (or by the date the UK leaves the EU without a deal). It allows people to stay indefinitely, unless they leave the UK for more than five years.

Pre-settled status may be given to people who started living in the UK by 31 December 2020 (or by the date the UK leaves the EU without a deal) but have not yet lived in the UK for five continuous years. It allows them to stay in the UK for a further five years.

The House of Lords EU Justice sub-committee raised concerns in February 2019 that the scheme is overly reliant on digital and online platforms, and warned that the lack of physical documentation provided to citizens has “clear parallels” with the Windrush scandal.

The UK Government has confirmed that the EUSS will continue to operate in the event of a no deal. It states that “[t]he deadline for applying will be 30 June 2021, or 31 December 2020 if the UK leaves the EU without a deal”.

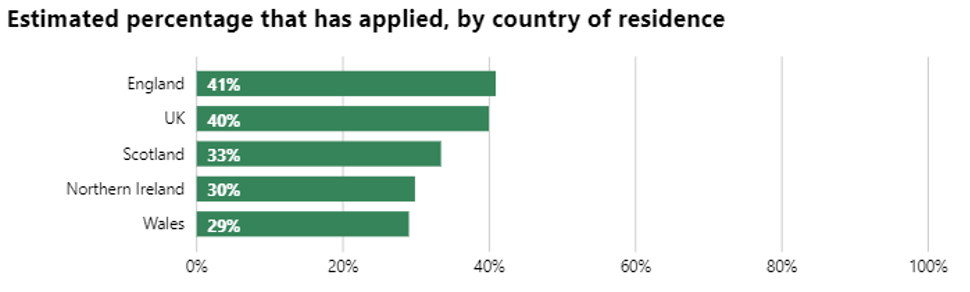

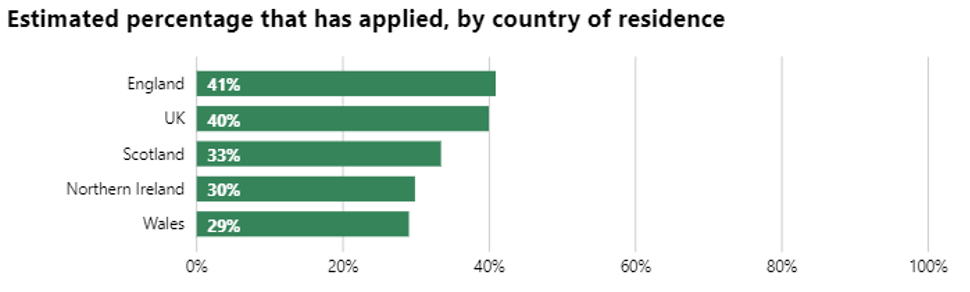

As of August 2019, 20,600 EU citizens in Wales had applied to the EUSS, which is approximately 29% of EU citizens (excluding Irish) currently living in Wales. This is the lowest proportion of all UK countries, according to the House of Commons Library’s analysis:

Source: House of Commons Library

Source: House of Commons Library

No deal

The UK Government published a new policy paper, No deal immigration arrangements for EU citizens arriving after Brexit on 4 September. It states:

“free movement as it currently stands under EU law will end on 31 October 2019. However, Parliament has provided that much of the free movement framework will remain in place under the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018 until Parliament passes primary legislation to repeal it.”

It is not clear when the UK Government will introduce the primary legislation.

The House of Commons Library’s analysis states that this means that “EU nationals could continue to come to the UK under what is essentially retained free movement law until 31 December 2020”, and would not be required to regularise their status until 31 December 2020.

The Library highlights analysis by Colin Yeo, an immigration barrister and blogger, who explains:

“In legal terms, although this is nowhere actually stated in the policy, it looks like the Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2016 which currently implement EU free movement law in the UK will be incorporated into UK law and continue in place whether the UK leaves with a deal or not. Almost exactly the same rules governing the entry and residence of EU citizens will therefore apply on 1 November 2019 as on 31 October 2019, come what may.”

European Temporary Leave to Remain (Euro TLR)

The ‘European Temporary Leave’ scheme’ (ELTS) was a policy introduced by Theresa May’s Government, but was re-announced under the ‘Euro TLR’ name by the Johnson Government (with some changes, detailed in this article).

It is aimed at EU nationals who arrive in the UK between 1 November 2019 and 31 December 2020 in the event of no deal.

It is a “voluntary” status, which allows people to stay in the UK for 36 months as a “bridge into the new immigration system”. This means that someone with Euro TLR would still need to meet the criteria under the future immigration system to remain in the UK after the 36 months expires.

Assembly scrutiny

In May 2019, the External Affairs and Additional Legalisation (EAAL) Committee held an evidence session on immigration after Brexit. It took evidence from Professor Jonathan Portes, Madeleine Sumption of the Migration Observatory at Oxford University (and member of the Migration Advisory Committee), Victoria Winckler of the Bevan Foundation, and Marley Morris of the Institute for Public Policy.

Over the summer the Committee called for evidence and held an online discussion to gather views on the White Paper proposals and the EUSS, and will continue its inquiry in the autumn term.

The new UK Government has committed to bringing forward its own proposals for a new immigration system, which will have to be in place by January 2021.

The challenge for Assembly Members and committees is scrutinising a fast-moving issue that directly affects people living and working in Wales, and has an impact on devolved public services, without having any direct power to change it.

*This is a fast moving policy area, so this information should be treated as correct at the time of writing.*

Article by Hannah Johnson, Senedd Research, National Assembly for Wales